On what would have been her birthday, we unpack the complexity of the feminist author’s legacy

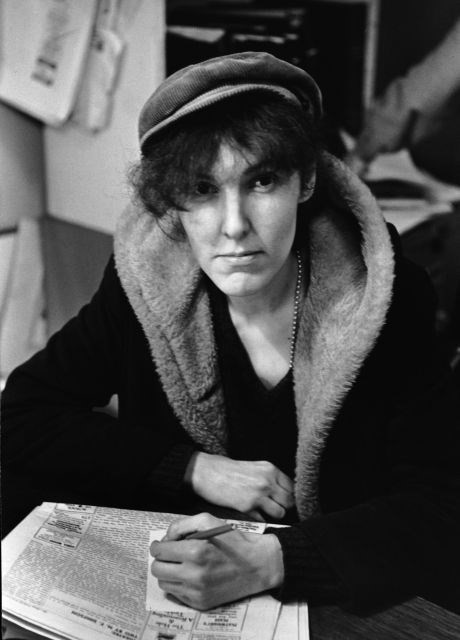

She was once declared “the Robespierre of feminism” by the celebrated writer, activist, and chronicler of American life, Norman Mailer. She was championed by the National Organisation for Women and hailed as “one of the most important spokeswomen of the feminist movement” by the radical lawyer Florynce Kennedy. But you’re more likely to know Valerie Solanas as the maniac who shot Andy Warhol.

She wasn’t a prolific writer, but her most notable work, the SCUM Manifesto, is one of the most uncompromising and controversial feminist tracts you’ll ever read. In what was initially a self-published text, Solanas called for the elimination of the male sex and the money system. It’s extreme and polarising, but it’s also acerbic, prophetic, and deeply relevant. She had something vital and prescient to say, but history has a way of subjugating women who refuse to behave. As the philosopher, Avital Ronell observed, when you’re a woman “your scream might be noted as part of an ensemble of subaltern feints – the complaint, the nagging, the chattering, the nonsense by which women’s speech has been largely depreciated”. The weight of history has reduced Valerie Solanas – with her righteous anger and searing intellect – to the caricature of a ‘schizo dyke’ and failed assassin.

Today marks the would-be birthday of Solanas, who was born in 1936. Without absolving or condoning her near-fatal attack on Warhol, I’d like to attempt to reconsider the life of Valerie Solanas with the same level of understanding and mitigation that’s been shown to so many of her male peers.

HER EARLY LIFE WAS TAINTED BY ABUSE AND HARDSHIP

In her brilliant study of art and alienation, The Lonely City, Olivia Laing reveals Solanas as a profoundly alienated figure, ‘radicalised by the circumstances of her own life’ and terminally alone. Growing up in New Jersey, Solanas’s youth was coloured by every shade of hardship. She was poor, she was abused, and she’d already given birth to two children by the time she was 16 (one by her alcoholic father and one by a sailor on leave – both babies were taken and raised elsewhere). As a teenager in the 1950s – an era of conformity and conservatism in American life – she suffered extreme bullying for defiantly coming out as a lesbian at high school. After graduating from the University of Maryland as a psychology major, she drifted around the country and ended up in New York, where she scraped by in the city’s boarding houses and welfare hostels – waitressing, begging, selling sex, and hustling.

The cumulative trauma of her young life placed her totally at odds with society – she’d experienced firsthand the brutality and inhumanity of the existing economic and social structures. And, having been exposed to the very worst aspects of the world around her, she was eternally and chronically unable to participate in it. That’s the emotional and psychological space from where, in the mid-1960s, she began writing what would become the SCUM Manifesto.

THE SCUM MANIFESTO IS A VITRIOLIC ATTACK ON MALE-PRIVILEGE

The SCUM Manifesto starts as it means to go on. The opening paragraph states, “Life in this society being, at best, an utter bore and no aspect of society being at all relevant to women, there remains to civic-minded, thrill-seeking females only to overthrow the government, eliminate the money system, institute complete automation, and destroy the male sex.”

She’s vitriolic about the structural violence enacted on women by men, and she makes it clear she’s not seeking a place within this existing structure – she wants to smash it up and start again. “SCUM wants to destroy the system, not attain certain rights within it.” There’s no compromise and certainly no prisoners.

To what extent she intended the entire manifesto to be taken literally and how much is pure provocation is debatable. But, despite what at times seems like hyperbole, it’s truly brilliant and relevant. Solanas’s concerns are legitimate, and it’s impossible not to be roused by her war cries. The SCUM Manifesto is the product of an engaged, erudite, and energetic mind writing with purpose and clarity – not the rantings of a “loony psycho-bitch.” It’s extreme and violent, but it’s also witty, provoking, and prescient.

“The SCUM Manifesto is the product of an engaged, erudite, and energetic mind writing with purpose and clarity – not the rantings of a ‘loony psycho-bitch’”

SHE WAS REJECTED EVEN BY THE OUTSIDERS

Solanas was confrontational, not conventionally easy on the eye, and really fucking furious. Nothing about her was particularly ingratiating but, although she detested society at large, she desperately wanted human connection.

She sought out Warhol and, in her own aggressive and odd way, tried to befriend him; pushing through his entourage and barging her way onto his table in the back of Max’s Kansas City. He was bemused by her brazenness and her quick wit and, for a time, they had a tenuous friendship of sorts. He apparently recorded some of their conversations and appropriated some of her lines for dialogue in his films. They even discussed staging Solanas’s play Up Your Ass – a critique of everyday sexism, as viewed through the eyes of a hustling, man-hating prostitute.

No doubt she saw Warhol’s celebrity as a way of lending her work more exposure but also recognised their shared attraction towards inversion and oddity. They were both anomalies in their unique ways.

But she was never going to assimilate easily into the Factory. Her appearance was totally at odds with the 1960s ideals of high-femme beauty fetishised by Warhol. Once the novelty of her presence wore off, he perhaps began to find her too abrasive and her political agenda too extreme. She made people uneasy. Rejected even by the so-called outsiders, she didn’t fit in anywhere. As Laing says, she was “an outlier and anomaly even amid the flamboyant freak show of the Factory”.

Despite this, Solanas wasn’t afraid to make a nuisance of herself. Social psychologist Erving Goffman once observed that most people’s lives are guided by the desire to avoid embarrassment – a condition he referred to as ‘wearing the leper’s bell’. Solanas, however, ran in the opposite direction. She continued to pursue and harass Warhol, long after he’d stopped accepting her calls. Though she wasn’t a natural exhibitionist, she was emboldened by a total commitment to the ideology she’d forged in the harrowing circumstances of her own experience.

THE CASE OF WARHOL VS SOLANAS

Having lost interest in the idea of being involved with Up Your Ass, Warhol also lost – or threw away – the manuscript Solanas had given him (referring to the script, he’d remarked bitchily, ”You typed this yourself? Why don’t you work for us as a receptionist?”). He offered her a role in his film I, a Man, but it didn’t make amends for discarding and deriding her play. Ronell describes the encounter between Solanas and Warhol as a case of the “low-tech writing apparatus” of the author coming up against “the reproductive panache of the Warhol machine”. Ultimately, the exchange amounted to not having being valued by Warhol. “She said time and time again Warhol hadn’t paid her enough attention,” writes Ronell. “She lacked credit and credibility… She was bereft, exploited, chronically undervalued.” Warhol was, in her eyes, the last in a series of men to subjugate and undermine her.

The dreadful culmination of events came in the summer of 1968 when Solanas was suffering from increasing mania and paranoia. On Monday 3 June, after plaguing him with phone calls and threats for several months, she emerged from the elevator into the Factory, pulled a 32. Beretta out of her bag, and fired at Andy Warhol as he chatted on the phone. He was rushed to a hospital where he underwent emergency surgery and, despite being clinically dead for 90 seconds on the operating table, his life was saved. Solanas’s life and legacy were condemned.

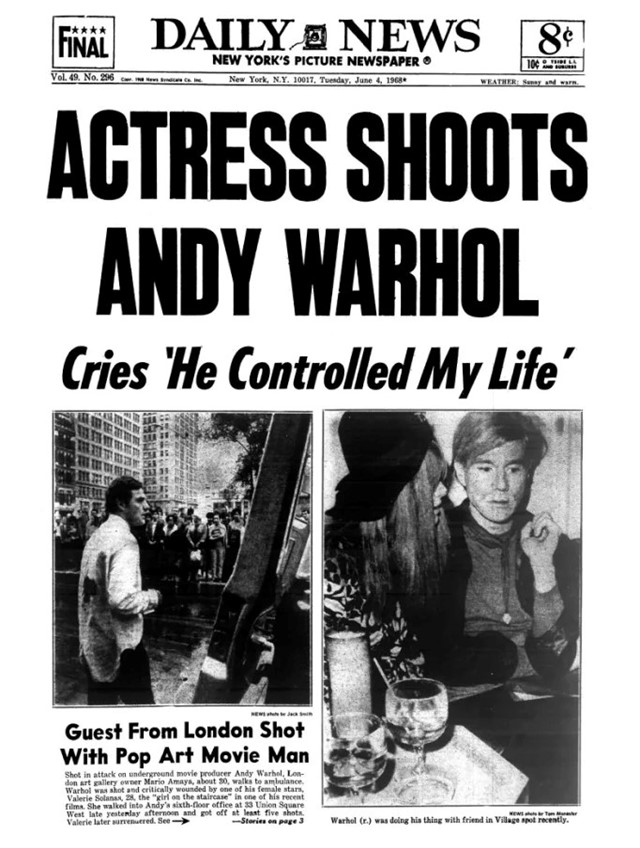

“ACTRESS SHOOTS ANDY WARHOL” WASN’T THE HEADLINE SHE WAS HOPING FOR

Typically, her big moment didn’t quite work out how she might’ve envisaged. After fudging her arrest (handing herself into a low-level traffic cop in Times Square) she finally found herself the centre of attention. Solanas urged reporters to read her manifesto, claiming, ”It’ll tell you what I am!” Apparently, none of them bothered, because the Daily News headline wrongly claimed: “ACTRESS SHOOTS ANDY WARHOL”.

In the immediate aftermath of her arrest, she received support from the feminist movement but she quickly and systematically rejected and alienated herself from all those who sort to join her cause, somehow unable to keep the followers she’d been seeking. People always distanced themselves eventually. And by the summer of 1969, when she was sentenced to three years in prison, the story had become as marginal as her very existence had been prior to committing the crime. The world had moved on, and the conclusion of the trial appeared in the New York Times alongside a notice informing readers of a change in the city’s garbage collection schedule.

Both Solanas and Warhol may have been “in the dumps” to see the status of their story reduced to actual trash, but Ronell points out the strangely appropriate correlation of these two headlines. “The garbage pile is where we wanted to land,” she says. “It’s the place from which Solanas was signalling, culturally rummaging … After all, one meaning of ‘scum’ throws us into garbage and we do not want to lose a sense of the excremental site to which Solanas relentlessly points and from which she speaks.”

SHE’S MUCH MORE THAN THE LABEL ‘SCHIZO DYKE’ PRESENTS HER

Admittedly, attempting to murder one of the most high profile artists of all time will cast a long shadow across your biography. But there does seem to be a huge disparity regarding the level of compassion Solanas has been granted compared with male writers and artists who’ve committed comparable (and often, arguably, worse) violent crimes.

In a statement issued on Facebook, the writer Chavisa Woods pointed out the unfair bias towards our judgement of Solanas. She draws a parallel with William Burroughs, who shot and killed his wife while they played an ill-conceived ‘game’ which involved him firing an apple off her head with a rifle, while high. Woods also highlights the cases of Pablo Neruda, Charles Bukowski, and Louis Althusser – all high-profile and revered figures known to have committed violence against women. Yet it doesn’t darken their door in the same way as Solanas’s crime has come to define her. In the case of Louis Althusser, the fact he strangled his wife to death only makes an appearance in the fourth paragraph of his Wikipedia entry. Burroughs received a suspended sentence, and Althusser was declared unfit to stand trial.

Despite being diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia, Solanas was given a three-year custodial sentence, during which time her womb was removed against her will, and she was moved between various brutal prisons and hospitals for the criminally insane. If the first half of her story was marked by loneliness and hardship, her life after prison was one of absolute isolation and deprivation. She died in San Francisco on 25 April 1988, destitute and despised.

Pity is probably the last thing she would want, which makes the pitiable story of Valerie Solanas all the more poignant. There have been attempts to tell her story with varying degrees of sympathy (she’s inspired several plays, a film called I Shot Andy Warhol, a Velvet Underground song, a novel, and an episode of American Horror Story in which she was played by Lena Dunham). But she’s largely immortalised as a ‘schizo dyke’ and defined by her attempt – and failure – to kill Andy Warhol.

Solanas is an icon of alienation; one of life’s uneven remainders, chronically unable to fit in. When your temperament is stubborn and perverse, and when your initiation into the world around you is so violent and unkind, it must mark you with the burden of terrible loneliness. As the SCUM Manifesto testifies to, Solanas was acutely aware of injustice in a way that others were not yet awaked to.